Behind the white farmhouse, past the giant puddle of mud, melting snow and tangled hose there is a hoop house filled with classical music.

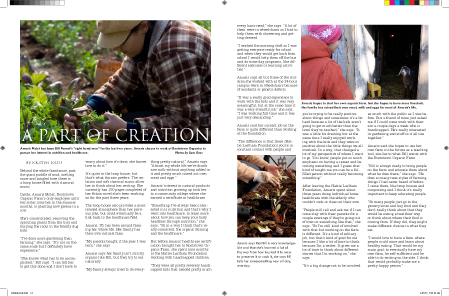

Inside, Amaris Mclat, Rootstown Organic Farm's only employee until her sister joins her in the summer months, is planting new greens in a row.

She’s concentrated, removing the sprouting plants from the tray and burying the roots in the freshly dug hole.

"I've done more gardening than farming," she says. "It's not on the same scale but I definitely have experience."

"She knows what has to be accomplished," Bill says. "I can tell her to get this done and I don't have to worry about how it's done, she knows how to do it.”

It’s quiet in the hoop house, but that’s what Amaris prefers. The isolation and soft classical music allow her to think about her writing. She currently has 150 pages completed of her fiction novel she’s been working on for the past three years.

The hoop house also provides a more relaxed atmosphere than her previous jobs, but could eventually be a link back to the healthcare field.

Amaris, 25, has been around farming her whole life. Her family has their own natural farm.

"My parents bought it the year I was born," she says.

Amaris says her family isn't strictly organic like Bill, but they try to eat naturally.

"My family always tried to do everything pretty natural," Amaris says. "Almost my whole life we've drank raw milk without anything added in it and pretty much raised out own meat and eggs."

Amaris’ interest in natural products and nutrition growing up took her to a community college where she earned a certificate in healthcare.

“Something I’ve always been interested in is nutrition and that’s why I went into healthcare, to learn more about how you can keep your body healthier through nutrition,” she says. “So in a way I think that’s really connected; the organic farming and the healthcare.”

But before Amaris’ healthcare certification brought her to Rootstown Organic Farm, she spent nine months at the Hattie Larlham Foundation working with handicapped children.

“They were all pretty severely handicapped kids that needed pretty much every basic need,” she says. “A lot of them were in wheelchairs so I had to help them with showering and getting dressed.

“I worked the morning shift so I was getting everyone ready for school and when they would get back from school I would help them off the bus and do some day programs, like different exercises or learning activities.”

Amaris says all but three of the children she worked with at the 24-hour campus were in wheelchairs because of accidents or genetic defects.

“It was a really good experience to work with the kids and it was very meaningful, but at the same time it was a very stressful job,” she says. “I was working full-time and it was just very demanding.”

Amaris said her current job on the farm is quite different than working at the foundation.

“The difference is that there (Hattie Larlham Foundation) you’re in constant contact with people and you’re trying to be really positive about things and sometimes it’s a bit hard because a lot of the kids aren’t going to get much better than the level they’ve reached,” she says. “It was a little bit draining but at the same time I really enjoyed working with the kids and they were so positive about the little things we all overlook. In a way, that changed a lot of my perspective of where I want to go. You know, people put so much emphasis on having a career and becoming something and I guess that kind of taught me you can be a fulfilled person without really becoming something.”

After leaving the Hattie Larlham Foundation, Amaris spent about three years doing individual home healthcare with the elderly who couldn’t cook or clean on their own.

“People still call and ask me if I can come stay with their parents for a couple evenings if they’re going out of town or something like that,” she says. “So I’m still kind of involved with that but working on the farm is different. It’s a kind of solitary job, but that’s kind of good for me because I like a lot of time to think because I’m a writer. It gives me a lot of time to think about different stories that I’m working on,” she says.

“It’s a big change not to be involved as much with the public as I was before. But a friend of mine just asked me if I could come work with their son a couple days a week who is handicapped. He’s really interested in gardening and stuff so it all ties together.”

Amaris said she hopes to use her own farm in the future as a teaching tool, similar to what Bill wants with the Rootstown Organic Farm.

“Bill is always ready to bring people on the farm and educate them about what he does there,” she says. “He does so many neat styles of farming, things I had never heard of before I came there, like hoop houses and composting and I think it’s really important to keep educating people.

“So many people just go to the grocery store and buy food and they don’t really think about that they would be eating a healthier way or think about where their food is coming from. If they did, they might make different choices in what they eat.

“I would love to have a farm where people could come and learn about healthy eating. That would be my main goal; to eventually have my own farm, be self-sufficient and be able to do writing on the side. I think that would probably make me a pretty happy person.”

|

ooo | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

One Ohio farmer hopes to use his organic farm as a teaching tool for students and “wannabe” organic farmers.

|

|||||||||

|

|||||||||

2010 © Sara Graca |

|||||||||